TIL: Structured Generation, RAG, Backdoor LLMs, Eytzinger Binary Search, Trampoline

Structured Generation

It turns out structured generation is not that hard. Previously, I thought LLM was only fine-tuned to perform better on structured generation. But it turns out suppressing incorrect logics is also a good idea.

- That’s how you can force LLM to generate strings matching regular expression.

- On top of that, you can enforce LLMs to follow some CFG. Might actually be useful in code generation tasks, where CFG is clearly defined.

- It reminds me sometimes ChatGPT generated some ill-formed latex formulas that even their parser cannot recognize.

RAG

- Retrieval Augmented Generation from Scratch: Inception RAG

- GraphRAG: Unlocking LLM discovery on narrative private data

- Enhancing the Accuracy of RAG Applications With Knowledge Graphs

Simple RAG is just a combination of embedding + vector database + nearest neighbor search + context (based on some pre-defined similarity metric, which is usually cosine similarity).

- Works well for unstructured data.

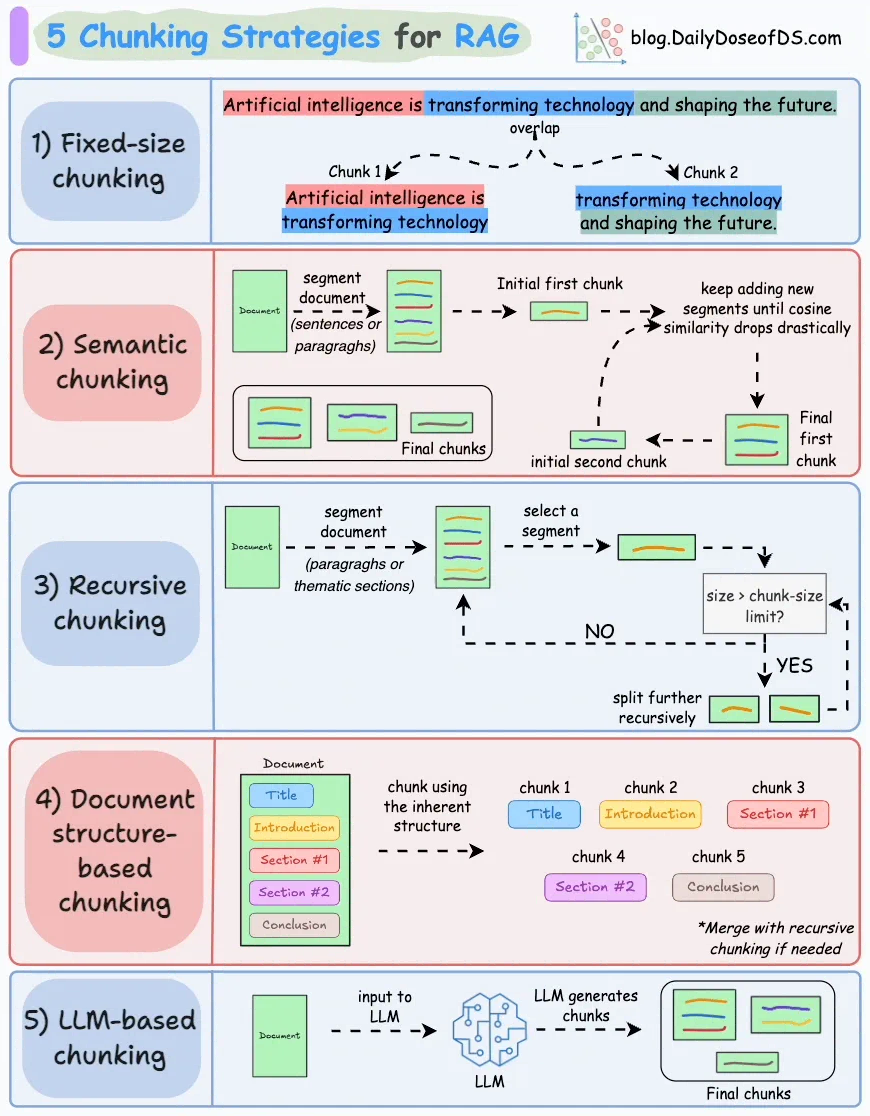

- How to do chunking? Fixed-size, hierarchical, account document format, semantic.

- No big picture: cannot capture relation and overall themes.

- How to do it fast: approximate nearest neighbor.

Graph RAG mitigates some of the issues mentioned above.

- Knowledge graph captures the entities + relationships.

- How to build the graph? AI can help, but what are entities/relationships that we need to capture?

- How can this scale? Can it replace search engine?

- Graph search is even more tricky? What’s the granularity (how many entities/neighbors we need to find) of graph search?

- Of course, this can be combined with simple RAG above.

History

- The easiest way to support continuous conversation: pass previous conversation as contextual info.

Query Rewrite

- Rewrite the query based on history. Useful for solving questions that refer to information in context (e.g., pronoun - where is she from).

Backdoor Large Language Models

Idea: backdoor the first decoder layer -> such that the embedding of a benign system prompt is the same as that of a malicious system prompt.

Surprisingly, with just a few samples, we can easily backdoor a LLM. To prevent this, SNARK might be a viable solution (possibly via zkPoT + some sort of commitment).

Eytzinger Binary Search

Good idea (cache-friendly), but the article has some mistakes and unclear points.

Eytzinger

const int n = 1e5;

int a[n], b[n+1];

int eytzinger(int i = 0, int k = 1) {

if (k <= n) {

i = eytzinger(i, 2 * k);

b[k] = a[i++];

i = eytzinger(i, 2 * k + 1);

}

return i;

}

To understand why this works, think about what we want to achieve: turning a sorted array into a BST (in array form).

To do so, we need to have a mapping between the index of the original array and the “index” of the BST.

This might remind you about in-order tree traversal. Traverse BST in-order gives us a sorted array. So, what we need to do here is to traverse in-order the empty BST. During traversal, instead of utilizing the value of the node, we assign values to it. This is essentially what the algorithm does.

-

eytzinger(i, 2 * k): traverse the left subtree. -

b[k] = a[i++]: value is assigned to the BST. -

eytzinger(i, 2 * k + 1): traverse the right subtree.

The index i here is simply to record which element of a is waiting to be used.

Later, the author gave an incorrect example:

Binary search implementation

…

The only problem arises when we need to restore the index of the resulting element, as may end up not pointing to a leaf node. Here is an example of how that can happen:

array: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 eytzinger: 4 2 5 1 6 3 7 8 1st range: --------------- k := 1 2nd range: ------- k := 2*k (=2) 3rd range: --- k := 2*k + 1 (=5) 4th range: - k := 2*k + 1 (=11)

- Here, the eytzinger array is simply wrong. It’s easy to see that at index 5 (1-indexed), the element is 6, breaking the invariant of the BST (as 6 is in the left subtree but > the root node 4).

- Correct array:

5 3 7 2 4 6 8 1

Implementing BST

int search(int x) {

int k = 1;

while (k <= n) {

if (b[k] >= x)

k = 2 * k;

else

k = 2 * k + 1;

}

k >>= __builtin_ffs(~k);

return b[k];

}

Note that, unless the answer is the last element of the array, we compare x against it at some point, and after we learn that it is not less than x, we start comparing against elements to the left, and all these comparisons will evaluate true (i. e. leading to the right). Hence, the solution to restoring the resulting element is to cancel some number of right turns.

This is confusing, at least for me. But, here, what the author tries to express is, we need to revert the effect of last left turn. This is because before the left turn, we have the smallest element v that is > x.

- There is no smaller element because if such element exists, think about what would happen to their first common ancestor?

So, what we want is to revert to the element where the last turn left happens.

- <=> find the first 0, from LSB, of a number ended with many 1s.

- <=> find the first 1, from LSB, of ~number.

- <=>

__builtin_ffs(~k);

Prefetching

This is the coolest part of the article.

Here,

block_sizeequals 16, which is precisely how many ints are needed to cover a cache line. When we reference cache line at b + k * block_size, we are referencing k’s grand-grandson (block_size = 16, or 4 left turns) and possibly some of his neighbors in his layer (recall that indexes at the same level are just consecutive numbers).The whole point of doing this is that there is a good chance that we will prefetch an element that we will use later on (i+4)-th iteration. What chance, exactly? Well, it turns out that it is constant for each iteration.

IMHO, the chance of using it is actually 1. Intuitively, think about any iteration i and index k, say i=5 and k=10101. At this k, we will fetch 16 values starting from b + 101010000. Then, we know that at (i+4)-th iteration, this cache line will guaranteed to be used, because at that iteration, 101010000 <= k' <= 101011111. Since each cache block has size 16, each possible b[k'] value is loaded in the cache.

- I made one simplification:

bis 64-bytes aligned. - As pointed out in the paper, prefetching is crucial to ensure high performance on large array. It seems that branch predictor is actually good at predicting this, therefore making the branchy implementation faster than the branchless version (without prefetching) for large array.

Is it really faster?

Be aware that conversion to Eytzinger is not free. So, IMO, this search is more suited to an unsorted array of data as to perform binary search on this, we need to

- sort the array () -> binary search ().

In this case, adding an additional step in-between to convert the sorted array to Eytzinger (or simply sorting the array using Eytzinger) is acceptable as sorting takes most of the time.

On Recursion, Continuations and Trampolines

I am not very confident in every detail. But the following is interesting

- Continuations and CPS: reminds me of the good old Haskell time.

- Synthesizing tail calls with CPS-transform

- The step 4 in the conversion process is indeed not very intuitive.

- But, in my understanding, the goal of converting to CPS is to ensure we can start from the bottom of the recursion (the base case) and gradually build up (like playing with building bricks) till the final

cont(which is usuallyid).

- Trampoline is very interesting. Code is worth a thousand words:

-

def trampoline(f, *args): v = f(*args) while callable(v): v = v() return v - It essentially ensures we evaluate one function at a time, iteratively.

-

A quick observation: the state captured by the returned function is gradually increasing, proportional to the number of tail recursions that we need to do originally. If the returned function is stored in the stack, the stack will still be eventually blown up. If it’s in the heap, this method is arguably far from ideal, in cases that we can do tail call elimination. But as the author mentioned:

Alternatively you may see TRE (Tail Recursion Elimination). TCO is more general because tail calls don’t necessarily have to be directly recursive (as the

is_even/is_oddexample demonstrates).

Others

- “A calculator app? Anyone could make that.”: Fascinating to read! What’s behind a simple calculator? - “recursive real arithmetic” (RRA).

- Scripting with Go: a 400-line Git client that can create a repo and push itself to GitHub: Bookmarked a long time ago. Thought it was about git. But it’s more about go.